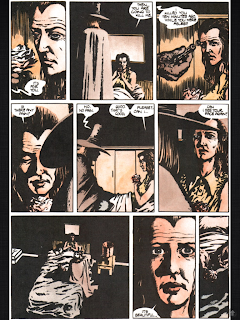

Transmetropolitan is a wonderful series, a real sort of 'classic' in my eyes (I'd read the series before this class, but seeing it on the resource list made me jump back onto it) about a Hunter S. Thompson kind of figure in the future, who breathlessly pursues truth and dogs corruption at the turn of every page. One of Warren Ellis's more prominent works, the energy just jumps right off the page.

The art is fantastic enough, but Ellis's writing is really what sells it as a story - the character of Spider Jerusalem being its own little microcosm of humor and sometimes not-so-subtle political commentary. Spider's 'Thompson' sheen extends so far as to have his own Nixon to battle with, as well as indulging in every other vice (as well as some that don't even exist yet) that Thompson did.

But merely framing Transmet's main dude as a caricature of Thompson is disingenuous, as Spider can clearly stand on his own two feet as an individual and as a harbinger of critical political commentary. Throughout the series, Spider comes across as not just a fabulously and hilariously-written bundle of explosive energy, but as a kind and fair intellectual, truly devoted to his self-described cause - even if it means shooting a few people with a bowel disruptor.

The sheer length of the series, as well, allows a great deal of stories and ideas to be imparted to the patient reader, making Transmetropolitan a pretty ace thing to endeavor soaking up. I certainly feel like a better person for making the leap and eventually devouring the whole thing.

Now the only thing I need to do is find the entire series again in a format that'll load onto my iPad.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)